APSU students unearth Clarksville’s forgotten Black history through research into 1900s

By: Ethan Steinquest February 6, 2024

A group of students at Austin Peay State University is uncovering forgotten stories about Clarksville's African American communities in the early 20th century, from a 103-year-old farmer to a robust district of Black entrepreneurialism on Marion Street.

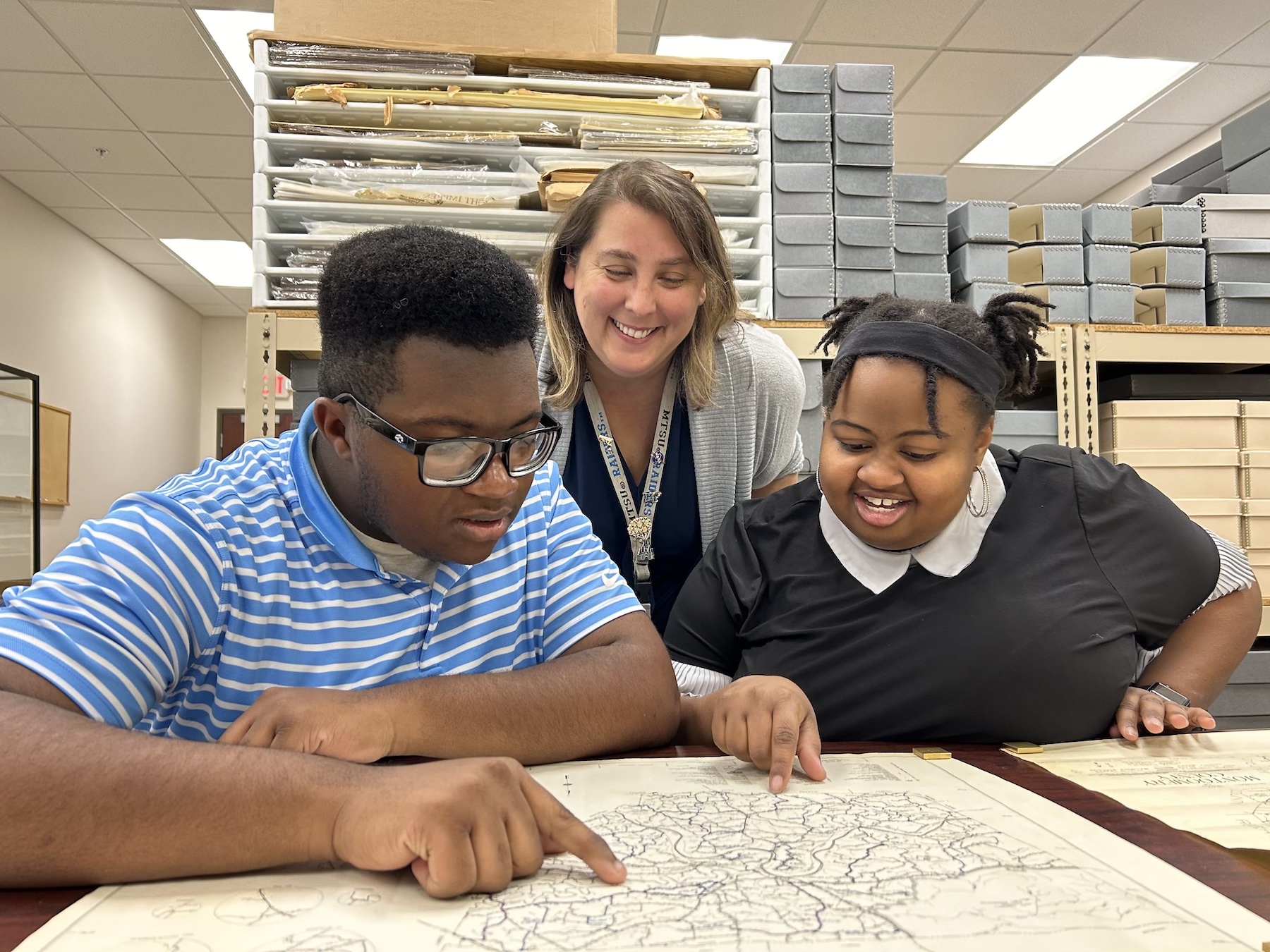

Under the guidance of Dr. Jessica Blake, assistant professor of history and philosophy, students spent the Fall 2023 semester compiling and analyzing Montgomery County census records from the 1910s and the 1950s. This semester, students are gearing up for a similar project focused on the 1890s, and the goal is to illustrate how Black commerce and culture evolved over time.

“Ever since I was a little kid, I really enjoyed history, but I was mainly fascinated with African American studies,” said junior political science major Derryus Shaw, one of the students who participated in the project. “The classes I took in high school were focused on the slavery aspect, but there’s more than that to African American history. There are a lot of people who left a huge impact and made a lot of contributions to the world.”

Blake said the research shows how the African American community played a significant role in Clarksville-Montgomery County’s economic development and how advances made during the civil rights movement impacted job opportunities.

“We tend to think of it as a rural economy based on farming and tobacco harvesting, but we also saw a lot of educational sites where there were households of teachers, and we saw jobs like ceramics producers,” Blake said. “That kind of variation represents the beauty of social history, and the students were able to get real hands-on experience in making sense of their community through historical records.”

The research is being used to support the Montgomery County Archives and the African American Legacy Trail, which is part of the nonprofit Mount Olive Cemetery Historic Preservation Society.

“For the last several years, I’ve talked to people about this idea and tried to get someone from Austin Peay involved,” said Terry Morris, the director of the African American Legacy Trail. “I ended up emailing Dr. Blake and told her I thought this was a great opportunity for her students to get some research experience and support the community.”

Students will also present their findings during a public forum from 5-7 p.m. on Feb. 18 at First Missionary Baptist Church, hosted in collaboration with the African American Legacy Trail and the Mount Olive Cemetery Historical Preservation Society.

“I think this is important because a lot of minorities are being ripped out of textbooks today, and this is a way for me to play a part in sharing their stories,” said Kamil Waddell, a junior history education major. “As someone who’s going to teach history in the education field, this [project] is something I can show my students one day and tell them I was a part of it.”

Maxwell Schaber, a graduate history major, said the research paints an intimate picture of Black life during the 1900s and offers valuable insights for the community.

“Of course, there’s a distance in time and the cold calculation of the census data, but when you’re going through the names, you realize these were all real people,” he said. “Something Dr. Blake brought up that I found very inspiring was how these names probably haven’t been read or looked at for decades, so we’re giving personal consideration to people who haven’t had that in a long time.”

The chance to learn more about individuals and their stories was especially appealing to Shaw, so he was eager to dig into the project.

“One of the people who really stuck out to me was a man named Ned Phelps,” he said. “He was a farmer, but the most significant thing about him was that he was 103 at the time. Once I came across that, I looked back at all the other people and noticed a lot of older people were still working in farm labor.”

Shaw said the institution of sharecropping was likely responsible for the number of African Americans laboring into retirement age. The system involved a legal arrangement between a landowner and a tenant farmer, who was able to use the land in exchange for a share of the crops they produced.

“That created a lot of problems, especially within the Black community back then,” he said. “If you’re a farmer, you’re giving the landowners all that you have and they’re not paying you what they owe, that puts you in debt. I see it as a generational curse because if one generation couldn’t pay off the debt, it was up to the next.”

Schaber, who focused his research on where Black communities were located, said segregation also had a clear impact on Montgomery County during the 1910s.

“I found what were essentially like islands of Black communities at the end of streets,” he said. “Another thing I focused on was the terminology they used to define these communities. In the late 1910s, they used the word ‘mulatto’ to define a biracial person, but that quickly changed to an overall Black term so they could better characterize them under Jim Crow laws.”

However, there were African Americans with prominent positions in the community during this era – such as Hiram Johnson, an artisan who carved many of the monuments visible in Clarksville’s cemeteries, and Nace Dixon, one of the city’s first Black aldermen.

Morris said Johnson offers an interesting case study into Black life in the community. According to a spotlight on the Montgomery County government’s Facebook page, Johnson (1852-1932) lived with English-born stone cutter Samuel Hodgson as a child and worked with the Hodgson family for over 50 years at their business, Clarksville Marble Works.

“Because of his relationship and apprenticeship with Samuel Hodgson, he seemingly had a high-profile lifestyle in the Clarksville community,” Morris said. “That dynamic is interesting and deserves more research. Peeling the layers back beyond his public life exposes the richness of diversity and its peculiar intricacies … this research will help paint a more vibrant picture of the county and how it developed to the present day.”

As the students moved into researching the 1950s, they also saw how the civil rights movement helped more African Americans take up visible positions within the community.

“You started to see mechanics, auto repairmen and all sorts of different careers,” Shaw said. “Another thing I noticed is that when it came to a woman and her role in the family [during the 1910s], it would either not have an occupation listed or it would have ‘housekeeper’ … but when you get toward the 1950s, you see people who are working as secretaries, librarians and jobs like that.”

Waddell said the 1950s census also reflected changing social attitudes based on the number of African American lodgers living in white households.

“A lodger is basically someone who helps pay bills in exchange for a roof over their head, and when people have lodgers in their houses or apartments, it signifies that they don’t make enough money to live there by themselves,” she said. “In terms of white people living in apartments with African Americans, I think it shows that they could put aside their differences and realize they both needed food and somewhere to live.”

Waddell, Shaw and Schaber are also among the students carrying the research project into the 1890s this semester, further illuminating the history of Clarksville’s African American community in the decades following the Civil War.

“The work of historical research is valuable to communities on a local level, not only to communicate but to make people more aware of the rich cultural and social history that existed around them before they were born,” Blake said. “And it’s also to raise awareness about the inequities that we’ve been working so hard this last century to fight against ... I think that we as a department are moving into the 21st century by getting our students involved in public history, and that's one of the ways we as an institution are really dynamic and forward-thinking."