APSU professor coauthors groundbreaking study on childhood lead exposure's long-term effects

By: Elaina Russell June 30, 2025

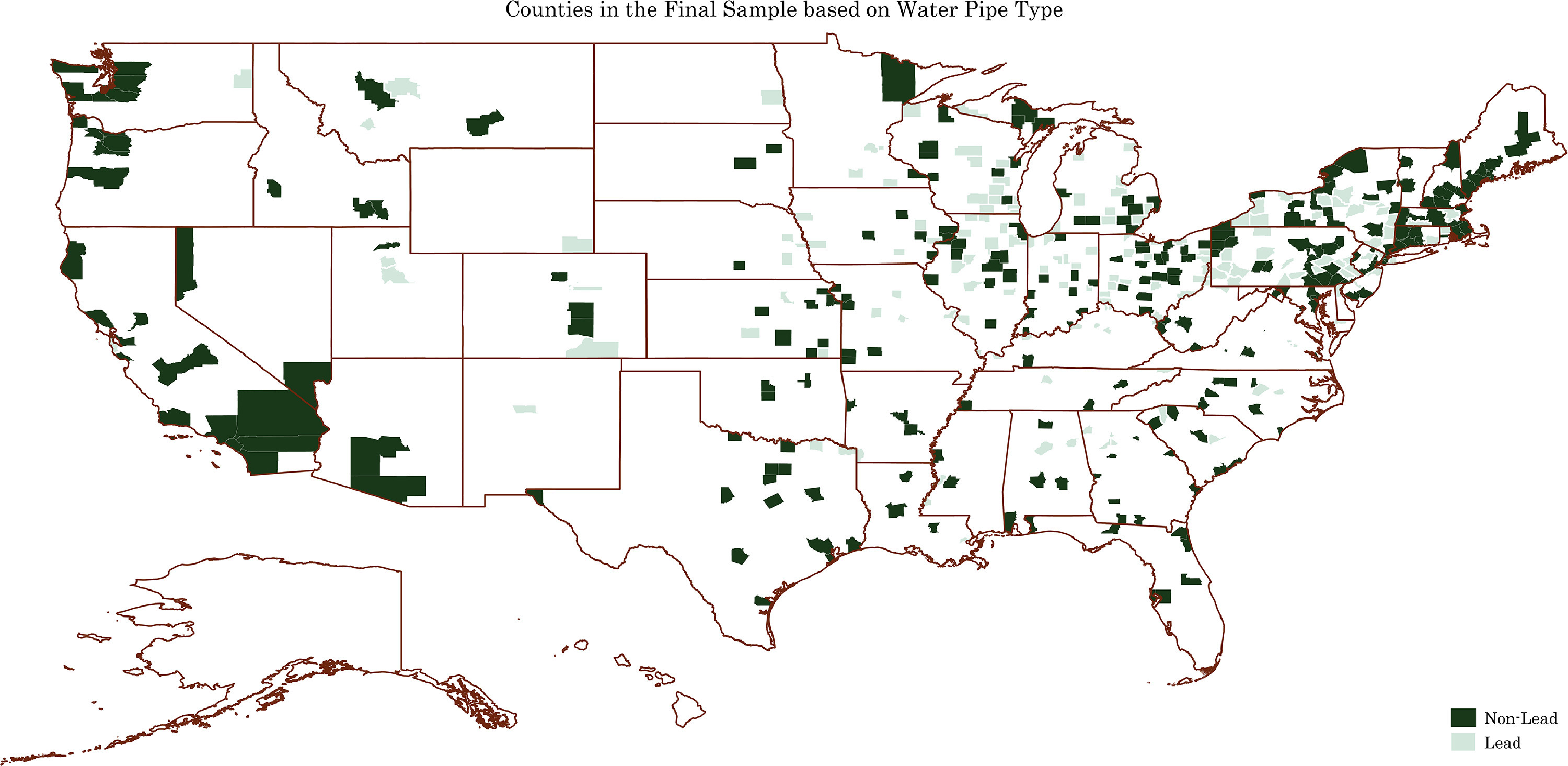

A map identifying lead vs non-lead cities in the final sample of a study coauthored by Dr. Hamid Noghanibehambari, an assistant professor at APSU.

CLARKSVILLE, Tenn. - A new study recently published in Explorations in Economic History suggests that early-life exposure to lead in drinking water is associated with a reduced longevity in men by approximately 9.6 months in cities with the most significant exposure.

Coauthors Dr. Jason Fletcher, professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Dr. Hamid Noghanibehambari, assistant professor at Austin Peay State University, believe they could be the first to link early-life exposure to lead and old-age longevity.

Fletcher and Noghanibehambari used primary data sources like the Social Security Administration Death Master Files for men who died between 1975 and 2005 and historical census data, among others, to conduct their study. The greatest impact is linked to individuals born in “lead cities,” locations associated with greater amounts of acidic water and older pipeline systems. Cities with higher automobile density using leaded gasoline during the 1940s are also noted to have increased risk. Their final sample size represents 783,483 individuals born in a lead city.

The study also found that lead exposure negatively impacts other important factors:

-

College attainment decreased by 29.6%

-

Wage reductions of 14.7%

-

Cognitive scores dropped by 6.3%

“Our findings highlight the lasting impact of early-life environmental risks,” Noghanibehambari said. “Childhood lead exposure didn’t just lower earnings and education—it shortened lives by nearly a year. These results show the serious long-term costs of past infrastructure choices and the need to invest in safer water systems today.”

The authors note that 90% of lead is stored in bones, based on existing research. This means exposure during childhood bone development increases the long-term risk as it is released into the bloodstream later in life when density decreases.

To provide greater context given the limited research on the long-term effects of lead exposure, they compare similar studies on male longevity during the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, as well as early-life exposure to agricultural chemicals and pesticides across the same period. The comparison revealed that the effects of lead exposure were an astonishing 3.8 times larger than those documented from the Dust Bowl. Early-life exposure to agricultural chemicals presented similar results, which reduced longevity by a year.

While studies on lead exposure aren't new, their findings present a unique perspective on the long-term effects of lead exposure. They note more recent water contamination crises in Flint, Michigan, and Newark, New Jersey, which suggest that some Americans are still at risk of lead exposure and its long-term effects.

“Our results demonstrate the long-term effects of infrastructure decisions in the U.S., which is especially relevant as local governments consider making large investments to replace lead pipes,” Fletcher said. “Our results suggest that these expensive projects may well pay off later on, in lives saved.”

While historical efforts have drastically improved water quality, Fletcher and Noghanibehambari conclude that further examination of long-term impact is needed, as some experts estimate between 15 and 22 million people are still using aging service lines in the U.S. containing lead.

This study contributes crucial knowledge to the ongoing body of research and offers substantial policy implications for mitigating the risk of long-term lead exposure.

Visit https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2025.101701 to read the full study, “Early-life lead exposure and male longevity: Evidence from historical municipal water systems,” by Drs. Jason Fletcher and Hamid Noghanibehambari, published in Explorations in Economic History.